In the fateful year of 1944, Otto Tief government’s attempts to restore the independence of the Republic of Estonia failed. In January 1944, the Soviet Union invaded Estonia, causing fear among the population that the Soviet regime, which preceded the German occupation (1941-1944), would be re-established. As a result of these events, approximately 70,000-80,000 people fled Estonia.

Below, the reader will find testimonials of the events of 1944, as well as analytical articles by historians.

A person, who had business in Helsinki and left Tallinn on Saturday, brought the following news. He is Estonian by nationality, is relatively well informed and evaluates events with some criticism, so his information is more or less verified. He explained:

'The Germans are serious about evacuating Tallinn and Tartu. There is a fear of airstrikes. In fact, it is difficult to carry out the evacuation because there are no trains or cars. People themselves don't want to leave, they say that if they are somewhere in the countryside, how will they get to the sea when they really need to escape. Some people still hope to get to Finland and Sweden.

The evacuation of Narva is the reason people don't want to leave the cities. People are afraid that their abandoned apartments will be ransacked, as happened in Narva. Its residents’ properties are already being sold in Tallinn. One thing is certain: if there is an evacuation, no matter where and how far, people can only rely on themselves. The Germans are not giving any transport aid to the civilians.'

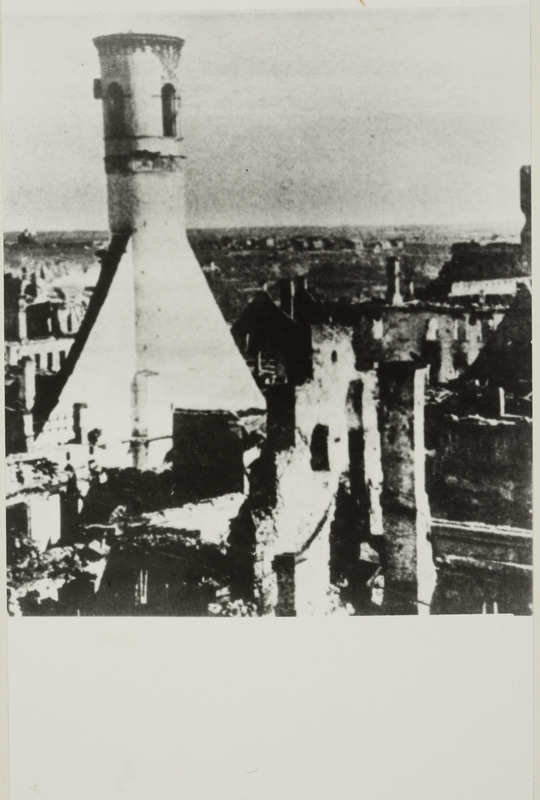

The Tallinn paper stated: On March 6, enemy planes attacked the city of Narva. After nine hours of bombardment, only piles of rubble and ashes were left of the city. A historic city fell into ruin. At first I was unable to think. My home – they have destroyed you! A home that was so dear to me! I have lost two loved ones – my father and now my home too! It can't be possible! The more I think about it, the more painful it seems! No, I don't want to think. I want to close my eyes and pretend it's just a nightmare! But I can't escape the reality!

At half past 7 in the evening, we suddenly hear the broken whistle of an air-raid alarm, immediately followed by the rumble of an explosion. An air strike! We experienced so many of them in Narva that I no longer feel the slightest fear! When I remove the blinds, I am blinded by the light pouring in from outside. There are 'Christmas trees', countless lighting balls! I remember Narva. Will this happen to Tallinn as well? Judging by the Christmas trees, this is a major attack. The house shakes terribly; there are more and more explosions. The windows rattle, threatening to fall in at any moment.

We go down to the basement. The hours drag on. Again, a sharp swish and a blast, the basement shakes. After a five-hour storm, the noise subsides and we exit the basement. /.../ We hear: 'Estonia is on fire!' - 'Harju Street is a mere pile of rubble!' From here, Tallinn looks like a sea of fire. From time to time, we hear a dark rumble, created by the collapse of burning houses. Blazing, flaming everywhere! Even the snow has a reddish glow, as though blood had soaked into it. How awful, so infinitely awful! The blaze could be seen from several hundred kilometres away, and a whisper echoed all over Estonia: Tallinn is burning!

Fearing that a similar attack could occur again, we decided to evacuate to We arrive at the station in the evening and wait for the Viljandi train. A clear and white night falls as the train pulls up. We get out baggage into the carriage and the train starts its journey, accompanied by our sighs of relief. Little Oti is sick; we try to make him as comfortable as possible.

It is 3 o'clock in the morning when we arrive at Viljandi station after a 24-hour drive. As it is still quite dark, we have to wait for daylight to set off on a 4 kilometre journey outside of the city. Although it is mid-March, the weather is unusually cold. The icy wind blows through the thickest clothes, making our teeth chatter. Valdar and I are pacing back and forth to get warm. I feel strangely heavy and dizzy.

The ERÜ32 car, whose task is to assist evacuees, drives to the station. To our greatest delight, we are to be taken directly to our destination. After half an hour's drive, we knock on the door of Veske farm. It takes a long time before they open, because everyone is still asleep in the early hour. We are immediately offered food and sent away to rest.

Today, 19 people arrived in Jollas, mainly from Tallinn. Most of them have left Tallinn on March 13, so after the bombing of Tallinn. Among the arrivals are the long-time architect of the city of Tallinn [Herbert] Johanson and his wife, and navy reserve captain-lieutenant Joh. Treiberg — both older men. They are on their way to Sweden. There was also a younger man from the oil shale industry. […] The following statements were given about the bombing of Tallinn:

'Before the last bombing, there was an air alarm test in Tallinn. A general exercise was carried out for all air defence forces. Another alarm test was supposed to be on the night of the bombing. This was known to civil servants and the authorities, and when the air alarm came, many considered it a mere test. People didn't go to the shelters. This caused a lot of confusion as well as casualties. All alarm signals are broken now, and the approaching danger will be announced by a total of five shots from the cannons.

The bombs were already falling after the first sounds of the alarm. Everyone agrees that the air defence was weak. Flak worked at first, and when its contingent was released, the air defence fell silent. During the second attack from 1a.m to 4a.m, the air defence was not working at all. Huge fires broke out; all the wooden house districts began to blaze. The planes descended relatively low. Shots were also fired from on-board guns. Although the bombs were dropped randomly, there were some attempts to hit targets. The power plant was hit hard. There were 18 bomb craters in the morning and one bomb had fallen between the new and old power plant. The power plant remained intact.'

“In my opinion the mobilisation has to take place immediately. The relations between Estonia and Germany can be sorted out in the future. We need the military might just now. If the communist power conquers our country and nation then everything will be lost. Then the Estonians will not be able to mobilise themselves nor organise anything.”

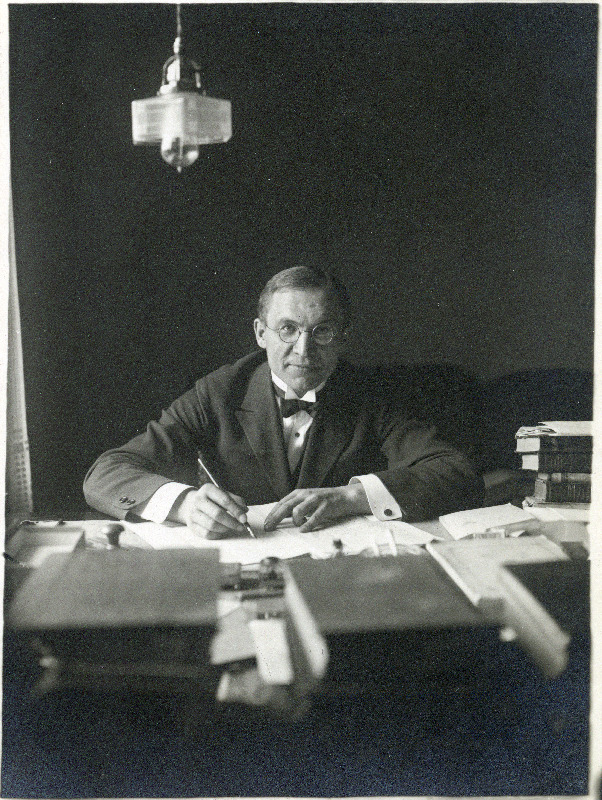

80 years ago, on 7 February 1944 the last legal Prime Minister of Estonia before the Soviet annexation Jüri Uluots gave an interview that turned out to be one of the most important broadcasts in the history of the Estonian Broadcasting Company. In the following days it was published or referred to in most of the Estonian newspapers. The quote above summarises the main idea of the interview.

Declaration of Mobilisation

Uluots had been keeping a low profile after the German occupation authorities rejected the conditional proposal for cooperation implicitly made in the name of the Republic of Estonia in the summer of 1941. After that he had dismissed all the German proposals for substantive or propagandistic cooperation. However, he had not participated directly in the activities of the hitherto passive national resistance groups either.

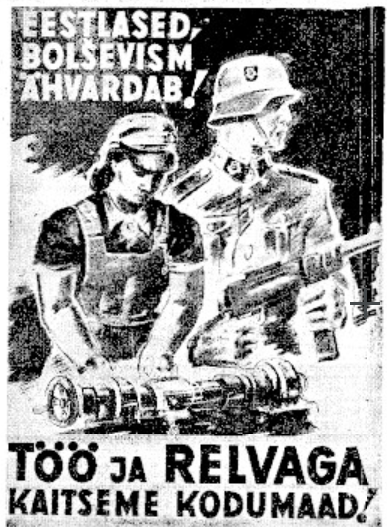

Since Uluots had been inactive for some time his public appearance in February 1944 was significant, but his message was even more important – Estonians should take up arms to defend their country against the Soviet occupants. More specifically, Uluots supported the general mobilisation of men born in 1904-1923 announced by Head of the Directorate of the Estonian Self-Administration Hjalmar Mäe on 31 January 1944. The general mobilisation also included some special categories, e.g., officers, military surgeons etc.

The wording of the mobilisation order was quite strange. In fact, it was a top-notch propaganda document without any hint to the actual operators – the Germans: “The defence of the Estonian land and people against the attacks of Bolshevik Russia demands the readiness of all able-bodied men for armed struggle. To this end I shall order the following:

§ 1. All men born in 1904-1923 who were citizens of the former Republic of Estonia before 20 June 1940 shall be mobilised into Estonian army units…”

Possibly, there were some who actually believed that the “Estonian army” was being formed but it was clearly a minority. A more attentive reader of the news must have noticed that the mobilisation orders were issued by Inspector-General Oberführer Johannes Soodla, who was actually the local recruitment officer for Waffen-SS. At the same time Soodla was appointed Commander of the Reinforcement Unit of the Estonian Waffen-SS.

In reality the mobilisation was carried out with the approval of Adolf Hitler, under the orders of SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and the general leadership of Higher SS and Police Leader in Ostland Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln. The latter authorised Inspector-General Soodla to carry out the mobilisation. The involvement of the Directorate of the Estonian Self-Administration and its Head Hjalmar Mäe added the process some Estonian flavour but had no practical role in the whole thing.

Although an average recruit was not an expert of international or constitutional law the general understanding was that Hjalmar Mäe had no direct or indirect authority to declare the mobilisation in the name of the Republic of Estonia. Presumably the majority of the recruits realised that it was a German mobilisation, just ostensibly organised by Estonians.

This called into question the success of the mobilisation right from the start, and the Germans probably sensed this as well. In the last months of 1943 Generalkommissar Litzmann had made it clear that the planned mobilisation would not be a success unless some political concessions about autonomy were made to the Estonians. Thus, 15,000 troops were allowed to be mobilised in Estonia, although the number of men born in those years was considerably higher (ca 80,000 and half of them could have been taken to active service immediately).

The Waffen-SS wanted to complete the 20th Estonian SS Division with younger conscripts. It was not clear what was to be done with the rest of the men. The initial plan was to put them at the disposal of the Commander of the Rear of Army Group North (Nord) to form three border defence regiments. But this question also remained unsolved for the time being, since nobody knew how many men would turn up. The Red Army offensive at the Narva front also influenced the plans – the first completed units of the fresh recruits were sent almost straight to the front (regiment “Tallinn” already on 12 February).

Impact of Jüri Uluots’s Interview

Obviously not all the conscripts were summoned to the recruitment offices on the same day. They had to report for duty depending on the year of birth between 3-11 February. The beginning was quite slow. According to memoirs, the men were not inclined to rush to the recruitment office on the first day, instead there were meetings and discussions, à la, “Let’s wait and see”. At least statistically, the interview by Uluots seems to have made a strong impact. By 8 February more than 10,000 had reported at the recruitment offices, on 11 February the total number exceeded 20,000, on 19 February – 30,000 and on 25 February the total number of recruits was more than 35,000.

Officially the mobilisation was scheduled to end on 11 February. But since many of the conscripts had decided to come at the last moment the recruitment offices were overwhelmed and could not receive them all. Many were advised to come back after a few days, and even longer exemptions were granted lightly. Draft dodgers were not actively pursued and punishments were quite lenient.

Obviously the words of Jüri Uluots, the legal representative of the Republic of Estonia, carried weight with the people, all the more so that he had not compromised himself by cooperating with the occupying forces. Most probably the people of Estonia understood that arguments over the lawfulness of the mobilisation and the legal status of the Republic of Estonia could wait. The Germans were what they were, but no-one wanted the Bolsheviks from the East back in power.

It should be noted that a certain activation of some hitherto passive resistance groups (e.g., in the tonality of leaflets) can be observed in 1943 in connection with the first forced recruitments carried out by the occupying forces. This was probably the reason why some people felt disappointment when hearing Uluots’s words. Among these were definitely members of the Estonian foreign delegations whose task was lobbying for the restoration of free Estonia in the capitals of Western democracies. Given their tasks, they were against any cooperation with the German occupation authorities, let alone support for general mobilisation.

In Estonia the views were somewhat more pragmatic. One of the results of the mobilisation (and the speech by Uluots) was the consolidation of the Estonian national opposition. On 14 February the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia was founded. It came behind Uluots's views on mobilisation, recognising that the Estonian people were forced to actively participate with the German army in the fight against the Eastern invaders. Still, the National Committee emphasised that any political union or cooperation with Germany was out of the question and the struggle must not alter Estonia’s orientation towards the West.

In conclusion, without trying to be wise in hindsight about the course of events that followed, Uluots’s interview played an important role in the success of the mobilisation. But it should not be overestimated either. A great portion of people went to defend their homeland without any external pressure. Probably every man who had received the call-up notice also carefully read it through. One must not forget that it was a wartime order and failure to comply with it would have been judged by wartime law.

Finally, also public opinion played an important role and after a short period of hesitation people started to support the mobilisation. It was even more important in rural regions where evaders were probably not reported but had to suffer from disparaging attitudes by the neighbours whose family members had gone to war.

One last glance at our home and the car is already rushing down the highway. – We’re leaving! I am sitting here with mother and 7-year-old cousin Oti; by chance, we managed to hitch a ride in a gasoline car.

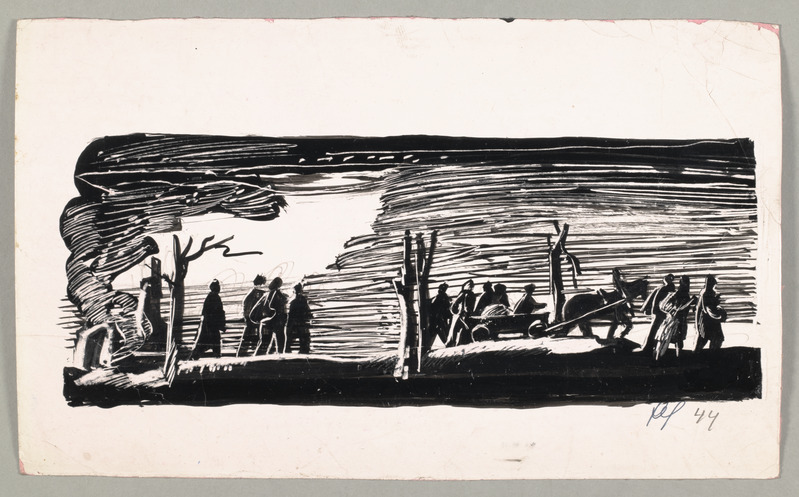

The highway is full of refugees, some on foot, and some on horseback, their belongings piled on a cart and a cow tied to the back. There are refugees from Narva and from the surrounding villages, Estonians, Russians, Ingrians! And in the middle of this, the retreating army, military cars, motorcycles, tanks...

It's impossible to get through! The car has to move together with foot travellers, unable to make room for itself.

Our initial destination – Sooküla – is about 20 kilometres from Narva, near Vaivara. Halfway there, the air fills with a terrible racket. We don't understand the reason for this at first, but then we see a scary image: Russian planes, there may be six or seven of them, are flying over the highway at a low level, shooting at the crowd. In the midst of frantic noise and cries of terror, they keep coming again and again, causing a terrible panic. People and horses are left lying on the road. In the blink of an eye, the crowd, maddened with fear, has thrown themselves down into the roadside ditches. The road is suddenly clear and the car quickly speeds away.

In 1944, the Russian troops of the Leningrad Front, Volkhov Front and the 2nd Baltic Front launched the Leningrad-Novgorod strategic offensive (14 January – 1 March) to crush the 16th and 18th Armies of the German Army Group North (Nord), to cut it off from the Army Group Centre (Mitte) and liberate the Leningrad and Novgorod regions (oblast). The attacks were carried out in several directions. The Kingisepp-Gdov offensive (1 February – 1 March) was aimed against Estonia, with the 42nd Army of the Leningrad Front and the 2nd Shock Army attacking first. After reaching the Narva River, the 42nd Army directed its main strike along the eastern shore of Lake Peipus. On 4 February, Gdov was taken, and in mid-February, an amphibious assault across Lake Lämmijärv followed. This event is not described here.

A breakthrough from the Narva front would have enabled the Red Army to advance quickly along the coast towards Tallinn. At best, this could have resulted in the German Army leaving Estonia because of the danger of becoming besieged. It would have definitely made it possible for the Baltic Fleet trapped in the eastern bay of the Gulf of Finland to get access to the entire Baltic Sea. Occupation of the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland would have probably made Finland step out of the war sooner. Since the German Army was suffering from a chronic lack of fuel, it was also important to maintain the oil-shale industry in North-East Estonia.

For the Red Army, the relatively short section of the frontline was a bottleneck where natural conditions made effective use of heavy equipment difficult. A wide breakthrough on the Narva River was possible only in winter when Lake Peipus and the large marshlands around it were frozen. The nearby Alutaguse primeval woods were unsuitable for the passage of technical equipment. There were only a few roads in the region. Most of the roads commencing from the Estonian eastern border ran towards the west along the seashore and the northern coast of Lake Peipus. The railway leading to the other parts of Estonia also began from Narva. Thus, the beginning of February was a critical period for the Red Army, if they wanted to break through the Narva Front, before the German troops that had retreated from Leningrad would be able to organise their defence.

Organising Defence on the Narva River

The offensive described above split the Wehrmacht 18th Army in two. On its left flank, the 54th Army Corps (Infantry General Otto Sponheimer) was forced back to the Narva River line and the 3rd SS Germanic Armoured Corps retreated towards Narva during the second half of January.

On 27 January 1944, both corps were united under the command of the 54th Army Corps staff and named the Sponheimer Group (Gruppe Sponheimer).

On 1 February 1944, the high command of the Army Group North ordered the Sponheimer Group to keep the bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Narva River around Jaanilinn (Ivangorod) and to take defensive positions along the line from the south of Ust-Chernova to the railway station of Slantsy. Also, an order was given to blow up the ice on the Narva River between Vasknarva and Krivasoo.

It was not possible to carry out the order completely, but the 3rd Armoured Corps succeeded in forming the Jaanilinn (Ivangorod) bridgehead, assuming the Red Army’s main strike would come from this direction. The attack came from four rifle divisions of the 43rd and 109th Rifle Corps along the main roads and railway. The German defence hung on and they left the bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Narva River only in July 1944.

The German divisions that had suffered significant losses and were in disarray were not able to establish efficient defence positions in other sections of the frontline. The situation was probably saved by the units of the Armoured Grenadier Division “Feldherrnhalle” that were rushed to the front on 1 February 1944. Initially they had been flown to the Tartu airfield and then moved to Narva by lorries.

Apart from the Jaanilinn bridgehead, the only more or less organised forces in the defence were parts of the 94th Security Regiment under the command of the 207th Security Division and the 29th–32nd Estonian Police Battalions. On 29 January, the latter were subjected to the commandant of the Narva Front and moved to the Jõhvi region. The 29th and the 30th Police Battalions were sent to fill in the gap to the south of Narva and the 31st organised defence at the Narva-Jõesuu region. The 32nd Battalion was used in coastal defence of the Sillamäe area. On 14 February, it took part in thwarting the amphibious landing of the Soviets at Meriküla.

There were more Estonian units at the Narva Front when the battles started. On 30 January, the reinforcement battalion of the Eastern Battalions was subjected to the command of Battle Group “Berlin” (the remains of the 227th Infantry Division), that was organising the defence between Narva and Narva-Jõesuu. In addition, Home Guard units were quickly brought to the coastal defence and to the rear of the Narva Front.

Red Army Bridgeheads

The first units of the Red Army reached the Narva River on 1 February. The next day, the troops of the 43rd Rifle Corps managed to establish a bridgehead to the north of Narva at Riigiküla and a bigger one in the Vaasa-Vepsküla-Siivertsi region. The defending German units were not able to prevent it, but the Red Army was not in a position to remarkably widen the bridgeheads either.

The Red Army was able to gain a better foothold to the south of Narva, in sections defended by the above-mentioned 29th and 30th Police Battalions (in the regions of Uusna-Vääska-Temnitsa and Omuti-Permisküla-Gorodenka, accordingly). Given the limited fire power and battle experience of the police battalions, as well as the lack of effective artillery support, it was only logical that the Red Army 122nd Rifle Corps broke through their sparse defence lines. Also, the German defence to the south of Narva collapsed, allowing the original Russian bridgehead to widen, resulting in the so-called Krivasoo pocket (Auvere bridgehead). The Red Army’s primary objective was to proceed from the bridgehead, cut off the road and railway connections to the west of Narva, and besiege the German units at the Narva River and its eastern bank. Initially the plan seemed to be successful and the Russians made it to the railway. However, the attack from Krivasoo was quickly averted by strong artillery fire.

Conclusion

The Red Army’s first strike on the Narva River in early February was successful. By the time the German military command could reorganise its lines, the Red Army had established several bridgeheads on the western bank of the Narva River. The bridgeheads north of Narva were liquidated by the beginning of March, but the Krivasoo bridgehead survived and endangered the rear of the German troops until the very end of the battles at the Narva Front. Fortunately for the defenders, the swampy terrain was extremely unfavourable for the Red Army to proceed, not to mention severe problems with logistics.

The German military command pulled itself together quite fast and took a number of simple steps to organise the defence. After the frontline was stabilised, the 227th Infantry Division covered the area between Narva and the sea. The Narva bridgehead was defended by the 3rd SS Armoured Corps. The 170th infantry division, the “Feldherrnhalle” Division and the 61st Infantry Division stood in defence opposite the Auvere bridgehead, and the 225th Infantry Division fought on the Narva River to the south of the Auvere bridgehead.

The peace is gone. It is rumoured that the enemy has began an air assault 10-12 kilometres from us. Here, deep in the forest, the rattle of a machine gun echoes so loudly, as if the battle were only a few hundred meters away. Worst of all, it seems to be getting closer by the hour!

Now, the planes are already flying over here too. The bomb blasts make the house shake and tremble. We are once again in the throes of war.

Finally a chance to leave the countryside behind! We are in the trunk of a car moving towards Jõhvi, planning to continue to Tallinn. It’s a particularly cold evening. The snow shines like silver in the moonlight. Beautiful, so divinely beautiful! But our eyes are blind to this beauty. We only feel that it is cold, terribly cold! Our bones and limbs feel heavy, the wind blows in our hair, and the body seems to be frozen. When, when will we get there?

We are a link in a long chain of cars. From time to time, the car in front of us suddenly stops due to a malfunction. Our car must also stop, then the one behind us and the whole chain. Another jerk and we stop. The car moving behind us has come too close. Now, unable to brake, it rushes forward...

We hear a rattle, the glass breaks! We drive on, but the car behind us has stopped, its lamps and windows broken, and it soon disappears behind the curve.

Jõhvi. The lady who was driving with us takes us to her acquaintances. A warm, comfortable, well lit room – we haven't such a thing in weeks! We are given a soft sofa to sleep in. What a pleasure it is to feel comfortable and warm again! It reminds me of home. Dear Narva, will I ever see you again? Can I once again walk on familiar streets, see familiar people again? Grandfather, mother! Where are you now

I felt my eyes filling with tears and I couldn't stop – I had to cry!

There was a camp for Estonian war refugees in Jollas near Helsinki. There, Voldemar Kures, an Estonian journalist who had already escaped, questioned the new arrivals about the mood in their homeland.

11 February 1944. A middle-aged craftsman from Tallinn said the following: […] 'The broadcasting announced several times that professor Uluots would give a statement on the radio. This announcement caught everyone’s attention and we were almost certain that Estonia's independence will be declared. Everyone gathered around the radios. I was in a bigger group when Uluots answered the first questions, and we were shocked and disappointed by what he said. Uluots’ statements had the opposite effect to what was expected. Everyone realised that the man had been forcibly dragged to the microphone. In these difficult times, people are constantly creating new illusions for themselves, and some think even now that this announcement might finally help us in some way.'

In the winter of 1944, there was a camp for Estonian war refugees in Jollas near Helsinki. There, Voldemar Kures, an Estonian journalist who had already escaped, questioned the new arrivals about the mood in their homeland.

A middle-aged craftsman from Tallinn said the following:

'The mood is inconsolable. If we go along with the losing side, we are facing doom, and if we stay with the Reds, we will all face the same fate.

As soon as general mobilization was announced, life nearly came to a standstill. Nobody wanted to do anything anymore. For example, the children's milk was not brought to the city. Then all saboteurs were threatened with the death penalty, and life somehow got going again. At first, everyone was against the mobilization. But where can you hide? Some still have to go. The depressing mood is evident by the excessive use of alcohol. I saw a group of men on the street who were brought from the countryside to one of the mobilization points. Behind the group, a drunken woman was playing a concertina. So this was “joining the army” with national flags and orchestras, as the propaganda newspaper 'Eesti Sõna' claimed! The mood is not nearly like it was when the Germans came, not to mention the days of the War of Independence.

It’s terrible that everything reminds me of the Reds’ occupation. The Russians forced our actors and writers to compile and recite verses for them, and now the German henchman Mäe orders the actors to recite patriotic songs and the poets to write 'patriotic' verses.'

The Germans and the municipality representatives are saying that friendly relations must be established with the people. They are glorifying former Estonian political figures. /.../ All this came to completely unexpectedly, even in this unusual time. Those who have been away from homeland do not know that the names of K. Päts, J. Tõnisson, General J. Laidoner and many other well-known figures from the time of independence were not allowed to be mentioned publicly during the Bolshevik nor the German occupation. The head of the Estonian Local Government [Hjalmar Mäe] issued a secret statement to the newspapers that forbade even describing how K. Päts, J. Laidoner, J. Tõnisson and others were deported to Russia by the Bolsheviks. Estonians learned about it from Finnish Estonian-language radio broadcasts. /.../ Now, the municipality and the German authorities are using new tricks. In the evening of 22 February, the President of the Republic of Estonia K. Päts, whose fate we currently know nothing about, was highlighted. It was the eve of his birthday. /.../ The glorification of K. Päts was truly overwhelming, and today's Independence Day commemoration takes place on the 70th anniversary of K. Päts.

In winter 1944, the Red Army arrived at the Estonian border again. By the end of the summer, it was evident that the Red Army would re-conquer Estonia and the terror that ceased in the summer of 1941 would continue.

On 14 January 1944, the Red Army groups of the three fronts started the Leningrad-Novgorod offensive against the German Army Group North (Nord) headed by General (Generaloberst) Walter Model. Their aim was the liberation of the Leningrad and Novgorod regions (oblast) and cutting off Army Group North from Army Group Centre (Mitte) that would enable the Red Army to reach the Baltic Sea. The offensive was successful and at Lake Peipus, the German units were cut into two. The left flank took positions on the line of the Narva River and the remaining army groups retreated towards Pskov.

The German Military High Command considered it vitally important to stabilise the frontline at the Narva River, because losing control of the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland would also have meant losing control of the whole Gulf of Finland, providing free passage for the Red-Bannered Baltic Fleet to the Baltic Sea. This in turn, would have caused grave danger for the whole Baltic coastline controlled by Germany. If the Germans had lost Estonia, the southern coast of Finland would have been open for attacks by the Red Army. As the German Army was suffering from a chronic lack of fuel and lubricants, it was of the utmost importance to maintain access to the shale oil production in North-East Estonia.

To restore fighting capacity, several German Army units were withdrawn, including many units that had been manned by foreigners. The completely demoralised 250th Infantry Division, better known as the Blue Division or the Spanish Legion, was removed from the frontline to the Tapa region and then sent home altogether. They were replaced by the 4th SS Armoured Grenadier Brigade Nederland formed by the Dutch and the 11th SS Armoured Grenadier Division Nordland that consisted of Danish and Norwegian volunteers. The German elite units were hurriedly deployed to Estonia by air to bear the brunt of fighting. The Wehrmacht Armoured Grenadier Division Feldherrnhalle arrived at the front already on 1 February. On 6 February, Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht Armoured Grenadier Division Grossdeutschland to be deployed to Estonia.

The Panther Line and the Evacuation of Civilians

By the end of January, the Red Army units under the command of General Leonid Govorov had lifted the Leningrad blockade and reached the frontiers of the pre-war Republic of Estonia in the region between Lake Peipus and the Gulf of Finland. On 25 January, Narva was proclaimed a frontline city and evacuation of the civilian population began. The Estonian borderline was not of any significant importance for the German command because the natural conditions at the line of the Narva River offered better positions for future battles. The Red Army units reached Narva River on 1 February, and the day after, they already established several bridgeheads on the western bank of the river.

For some time, the Germans had been making preparations for battles on the line of the Narva River and the west bank of Lake Peipus. These positions were part of the Panther Line (Panther-Stellung). The latter constituted a part of the East Wall (Ostwall) that stretched all the way from the Black Sea to the Gulf of Finland. The construction of the Wall had started back in August 1943, but it was far from finished and fortification works continued also during the battles. At the same time, defences were built along the North Estonian coast to push back possible attacks from the sea.

The evacuation of the civilian population from the region between the defence line and the front began simultaneously with the creation of the Panther Line. This was the first wave of war refugees in Estonia, called Operation Robot (Roboter). In addition to strictly military and humanitarian purposes, the operation, as its name suggests, was launched to attain labourers, which is in short supply in any country at war. Those that were unable to work had to remain on enemy-occupied territory. As a result, by 23 January 1944, more than 300,000 persons had been evacuated from between the still unfinished Panther Line in the rear and the frontline. Among them were Estonians who had lived on the eastern side of the Narva River and Lake Peipus, Ingrian Finns, and Russians. Tens of thousands of them also reached Estonia.

The compulsory evacuation of the civilian population of Narva began on 25 January and was probably unexpected for many of them. The German propaganda persistently tried to draw a more optimistic picture of the situation, while the reality was mostly reflected in rumours and the noise of battle could already be heard. The local press informed the population of the battles reaching the Narva River with some delay, while referring to possible temporary evacuation. On 3 February, the Eesti Sõna newspaper printed a speech by Hjalmar Mäe, Head of the Directorate of the Estonian Self-Administration: “When the enemy is close to the borders of our homeland, it may become necessary to evacuate some of the nearby settlements to keep people away from danger. Every Estonian must remain cool-headed and leave their home when ordered to do so without complaints. Every Estonian should also have a warm heart to give others shelter.” Even so, evacuation in Mäe’s speech was a side issue; he mainly focused on strengthening the morale of the fighters and encouraging mobilisation.

Preparations for the General Mobilisation

The battles that had reached the Estonian borders were the primary motive for declaring a general mobilisation. On 1 February, the mobilisation order by the Head of the Directorate of the Estonian Self-Administration appeared in newspapers and on billboards. It stated that according to the agreement with the German military authorities, all male citizens born between 1904 and 1923 had to report at the Defence Service Commissions as conscripts. Thus began the general mobilisation of the Estonian citizens that was against the laws of war, just as the mobilisation into the Red Army by the Soviets in summer 1941.

The mobilisation did not start out of nowhere. Estonian Home Guard had already carried out the registration of men of mobilisation age. In parallel with the registration of the men and planning of the formation of the units, a real mobilisation was also carried out in 1943, when conscripts born in 1925 were drafted.

Rumours about a possible general mobilisation had been circling among the population for several months. The security police’s reports on the mood of the general public indicated that the results of the mobilisation (including the attitudes towards it) would be unpredictable. The earlier mobilisations, whether carried out openly or not, gave reason to assume that avoidance would be massive.

The Germans were definitely aware of this problem. However, there were also factors which indicated that the mobilisation could be successful. It is reasonable to believe that an ordinary citizen at the time had no precise understanding of the “Byzantine nature” of the occupying forces or international laws of war. The Estonian institutions controlled by the occupying forces (the Directorate of the Estonian Self-Administration, Home Guard and Office of the Inspector-General) were used to raise the conscripts’ motivation to join. The mobilisation order also referred to the Republic of Estonia legislation and citizenship applicable before 22 June 1940. In addition, the Estonian national opposition, which had been relatively passive until then, came on board and agreed to support the mobilisation.

The clever propaganda conducted by the occupying forces was equally important for the success of the mobilisation. The motive of the Second War of Independence, used since 1941, did not glorify the Germans. Rather, it emphasised that in the struggle against eastern barbarism, there was no alternative to supporting the Germans.

The beginning of 1944 did not bode well. There were several turbulent changes ahead for Estonia, which determined its fate for the following decades. The fear of terror forced tens of thousands of Estonians to leave their homeland.

The fires of war have come terribly close, but half of Narva's population has stubbornly decided to stay put, despite the orders.

What followed was a most horrid night that decided our fate. Already in the evening, cannons were set up in the vicinity of Narva, and by dusk, a commotion broke out. We were utterly in the midst of war. Bullets fly back and forth across the city. The sky is like a sea of fire. It's a beautiful, yet gruesome sight. The explosions of aerial bombs make our house wobble as if it were made of cardboard! Fires will soon break out. In Narva alone, one can count 7-8 fires. We fear the Russians will march in before morning. We decided to leave the next morning before it’s too late. Even so, grandfather and grandmother wish to stay put.

Thus began our war journey.